TDIH: The Olive Branch Petition

On July 5, 1775, Congress was still appealing to the King for relief & trying to reconcile. On July 4, 1776, Congress approved the Declaration of Independence. What a contrast.

On this day in 1775, the Continental Congress approves the so-called Olive Branch petition. This action occurred one short year before the Declaration of Independence was approved.

What an interesting contrast. On July 5, 1775, Congress was still appealing to the King for relief and trying to reconcile. On July 4, 1776, Congress approved a document that would ultimately separate us from Great Britain forever.

Of course, in 1775, it wasn’t quite so apparent that a declaration of independence was necessary. Despite the bloodshed at Lexington and Concord, some Americans still wanted to reconcile. They considered themselves British. Others weren’t so sure.

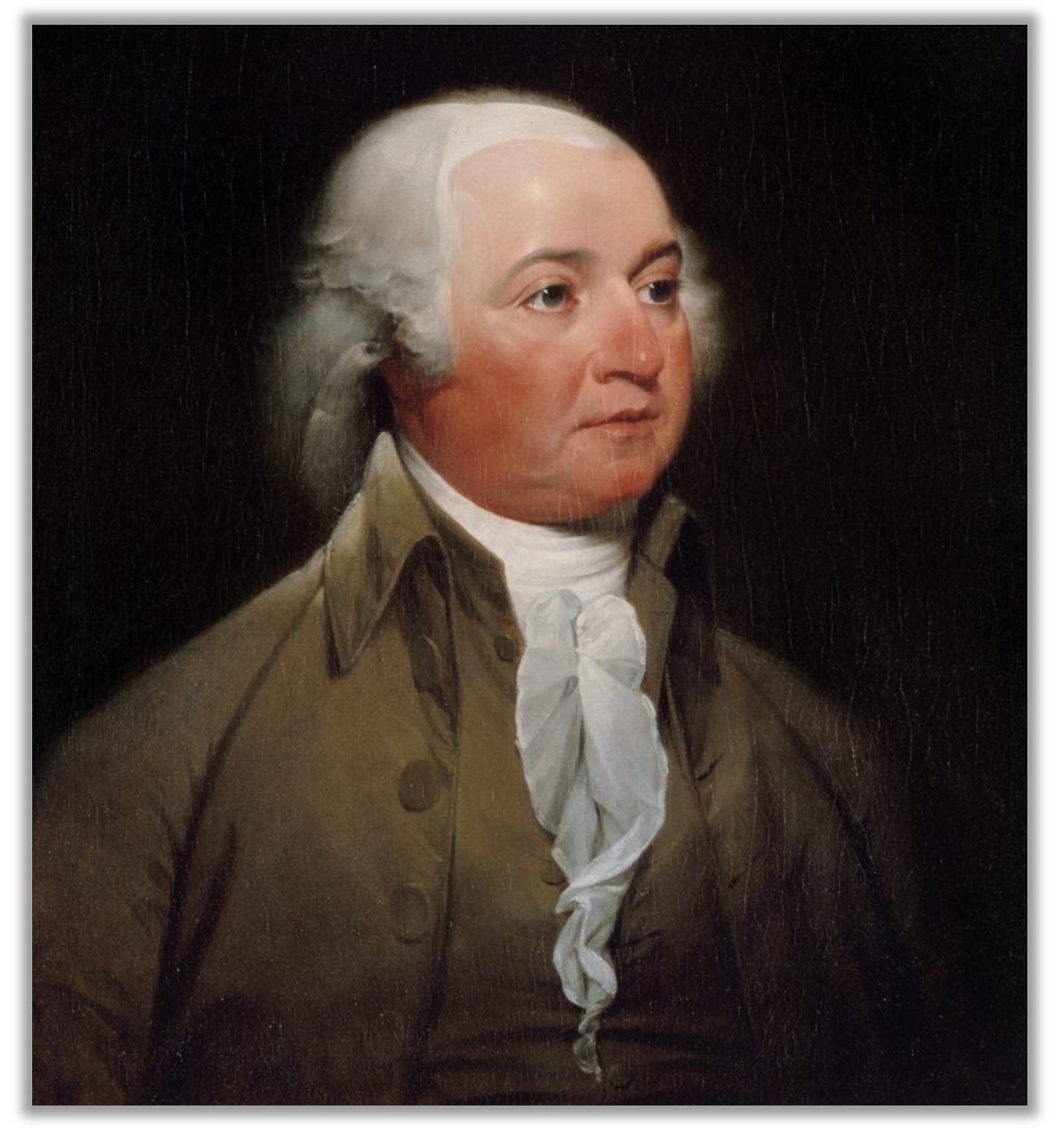

Thus, the “humble petition” approved by Congress was a bit of a compromise. In fact, at least one important delegate thought the petition was a complete waste of time. Some people, John Adams wrote, “cannot be perswaded to think that it is so necessary to prepare for War as it really is.” The colonies should be preparing to defend themselves. “Powder and Artillery,” he concluded, “are the most efficacious, Sure, and infallibly conciliatory Measures We can adopt.”

Whatever Adams might have thought, Congress voted for the measure. A petition was thus drafted, approved, and finally signed on July 8.

The petition blamed Parliament, not the King, for the problems between England and the colonies. The colonists spoke of themselves as “your majesty’s faithful subjects” and expressed hope and confidence that the King would act to grant relief.

Adams went along with the compromise, but he wasn’t too happy about it. He wrote a rather blunt letter about John Dickinson, who had been pushing for the petition. Dickinson, he wrote, is a “piddling Genius” who “has given a silly Cast to our whole Doings.”

That proved to be a mistake. Although Adams had intended for the letter to remain private, it was intercepted and published in Tory newspapers. Dickinson wasn’t too happy, as you can imagine. In fact, he gave Adams the cold shoulder the next time they met. Because Dickinson was well-respected, others refused to talk to Adams as well.

This went on for weeks. Adams later wrote that he was “avoided, like a man infected with the leprosy,” and he felt “borne down by the weight of care and unpopularity.” Benjamin Rush also noted of this time period that Adams was “an object of nearly universal scorn and detestation.”

Yikes.

In the end, Adams was proven right. A copy of the Olive Branch petition arrived in London by the end of August, and it was formally presented to the King. Not that King George cared! He didn’t believe that the colonists were sincere. He’d already issued a proclamation declaring the colonies to be in “open and avowed rebellion,” and he refused to so much as look at the petition.

The Olive Branch Petition is a remarkable contrast to the Declaration of Independence, which was approved only one year later. The mindset of the colonists had changed drastically in just 12 short months. In the petition, the colonists called themselves “subjects” and expressed hope that the King would help. In the Declaration, they blasted the King for “an absolute Tyranny over these States.” They concluded:

“We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America . . . solemnly publish and declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States.”

Still so true today, isn’t it?!

Sources can always be found on my website, here.

I think it really was a step in the right direction to offer peaceful resolution for more than just that resolution. The King's response was only an affirmation of what was done on July 2 and then declared openly on the 4th of July, 1776.

Thanks for this wonderful story, Tara!

I'm sure Adams didn't mind being proved right either!