TDIH: Declaration on Taking Up Arms

“We will, in defiance of every hazard, with unabating firmness and perseverance, employ for the preservation of our liberties; being with one mind resolved to dye Free-men rather than live Slaves.”

On this day in 1775, the Continental Congress approves a Declaration on the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms.

Wait. Congressional delegates had approved an Olive Branch Petition to King George only one day earlier. (See yesterday’s post.) One day they are petitioning for reconciliation and the next day they are justifying their use of arms? What was going on?

At this point in time, it had been more than two months since the “shot heard ‘round the world” at Lexington and Concord. The Continental Congress felt that it was time to issue a declaration, explaining why Americans had taken up arms against their mother country.

Of course, the process of drafting this Declaration wasn’t entirely smooth. Tension still existed between those Americans who wanted to reconcile with Great Britain and those who thought that attempts at reconciliation would be futile.

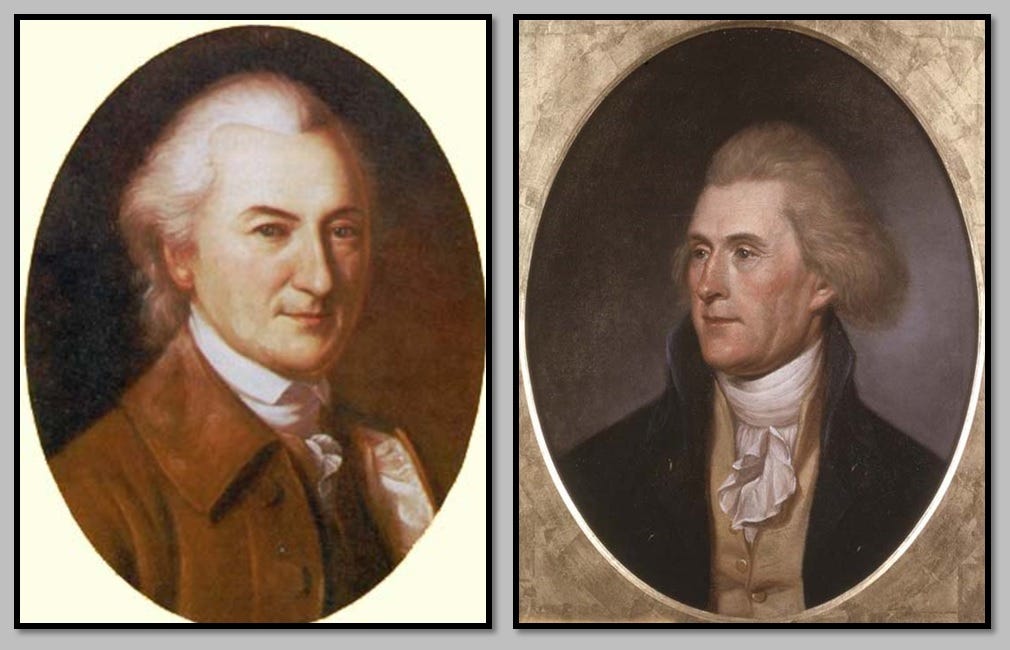

The first committee appointed to write the Declaration didn’t quite get the job done, so Thomas Jefferson and John Dickinson were added to the committee. Jefferson, of course, would go on to author the Declaration of Independence. Dickinson was the man who had pushed for the Olive Branch Petition. He was very upset at Parliament, but he still hoped to reconcile with the King.

Jefferson took the first stab at a draft. “It was too strong for Mr. Dickinson,” Jefferson later wrote. “He still retained the hope of reconciliation with the mother-country, and was unwilling it should be lessened by offensive statements. . . . We therefore requested him to take the paper and put it into a form he could approve.”

Dickinson drafted a statement that was almost entirely new. He kept only a few paragraphs of Jefferson’s original. Interestingly, Dickinson made the section about Parliament’s abuses harsher, but then he softened the Declaration by adding a section specifically denying an American desire for independence.

As approved by Congress, the Declaration spoke of a Parliament that had claimed too much power. “What is to defend us against so enormous, so unlimited a power?” asked Congress. “Not a single man of those who assume it, is chosen by us; or is subject to our controul or influence.”

“Our cause is just. Our union is perfect,” the Continental Congress concluded. Thus, “we will, in defiance of every hazard, with unabating firmness and perseverance, employ for the preservation of our liberties; being with one mind resolved to dye Free-men rather than live Slaves.”

The pleas in both the Declaration and the Olive Branch Petition would fall on deaf ears. The Declaration of Independence would follow only one year later.

Sources can always be found on my website, here.

Those who rule over a people from a distance rare ly take the time to understand the people they are making decisions for. Rather they mandate for their own benefit rather than ruling for the local benefit with little recourse by the people affected. That is why it is important to elect a President who has won the approval of individual States through the Electoral College. The Capitol of the US may be in the US, but their thoughts are on power and might as well be a million miles away.

Thank you Tara. It is easy to understand just how difficult it must have been for the Colonists to split from the British Crown and then, to prepare for war against the Motherland, which had the world's greatest armed forces.

People such as John Dickinson hadn't yet reached the point of irreconciliation. Others felt that the point of reconciliation had already past based on the actions of the King. Obviously, the decision was made after enough people joined the side of freedom and independence.

Your history lessons are spot on Tara, with just the right amount of detail and facts.