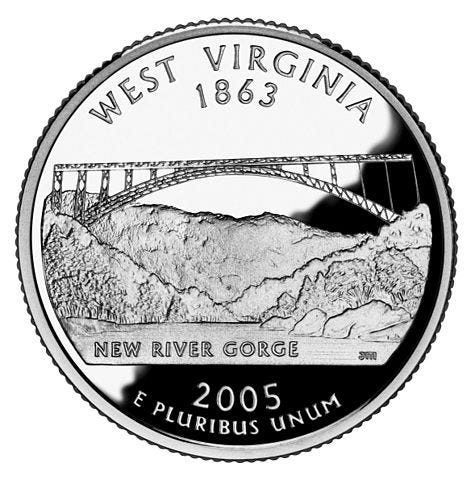

TDIH: West Virginia becomes a state

At the time, some questioned whether West Virginia—formerly a part of the State of Virginia—could legally be admitted as a state without Virginia’s consent.

On this day in 1863, West Virginia is admitted into the Union. At the time, some questioned whether West Virginia—formerly a part of the State of Virginia—could legally be admitted as a state without Virginia’s consent.

Virginia, of course, had not consented. It was a part of the Confederate States of America at the time.

Regional tensions had long existed within the state of Virginia, but matters got much worse in April 1861. On the 17th of that month, a Virginia state convention voted to secede from the Union. The vote was 88-55, but the composition of that vote was lopsided: Most of the members hailing from the western side voted against secession.

Virginians on the west side of the state were irate. They called for two more conventions in Wheeling. The second of these conventions specifically repudiated the ordinance of secession and established a new government: the Restored Government of Virginia. Before long, these citizens had ratified a new state constitution and decided that they wanted to form an entirely new state, West Virginia.

They had just one small problem: Article IV, Section 3 of the U.S. Constitution provides that “no new State shall be formed or erected within the Jurisdiction of any other State . . . without the Consent of the Legislatures of the States concerned as well as of the Congress.”

Nevertheless, during the spring of 1862, a bill was submitted to the U.S. Congress requesting that West Virginia be admitted as a state. As proposed, the bill allowed West Virginia to join the Union, but it also required West Virginia to amend its constitution so that slaves within the state would be gradually emancipated. The Senate and House had both approved the bill by December 1862.

Lincoln spent time thinking about whether to sign the law. He asked his cabinet members for “an opinion in writing . . . 1st. Is the said Act constitutional? 2d. Is the said Act expedient?” Three of his cabinet members argued “yes” to both. Three argued “no” to both.

Ultimately, Lincoln decided to sign the measure. At the time, he wrote that the “consent of the Legislature of Virginia is constitutionally necessary to the bill for the admission of West-Virginia . . . A body claiming to be such Legislature has given its consent.” He did not deem the plural “Legislatures” (in the constitutional provision) to be problematic, at least not in this context. “Can this government stand,” he asked, “if it indulges constitutional constructions by which men in open rebellion against it are to be accounted, man for man, the equals of those who maintain their loyalty to it?” He believed the decision to be an expedient one: “We can scarcely dispense with the aid of West-Virginia in this struggle; much less can we afford to have her against us.” He concluded that the “division of a State is dreaded as a precedent. But a measure made expedient by a war, is no precedent for times of peace.”

Hmm. What do you think of that last piece of logic?!

Either way, West Virginia quickly ratified a revised constitution, providing for emancipation of slaves, in March 1863. On June 20, 1863, West Virginia was formally recognized as a state.

Sources can always be found on my website, here.

I knew of the reason for W. VA. to be separated from VA., but had never heard the wranglings that went on to make it happen. I would surmise that VA. was none to happy to lose that portion of their land mass! Thanks, Tara, for the lesson.

Everything Lincoln did to serve his purposes was questionable, and a lot of it was unconstitutional (like this!).