On this day in 1939, the crew of the USS Squalus is rescued. The day before, the submarine had sunk to a shocking depth: 240 feet. The rescue marked the first time that a submarine crew had ever been rescued beyond 20 feet.

It nearly didn’t happen on that day in 1939, either.

Squalus was then on the cutting edge of submarine technology. It was being tested just outside Portsmouth, New Hampshire on May 23 when it ran into trouble and sunk. (See yesterday’s history post.) Captain Oliver Naquin sent emergency buoys and rockets to the surface. Then he and his men huddled together in the cold submarine and waited for help.

When Squalus never returned to the shipyard, the commander realized that something was amiss. He sent Squalus’s sister submarine in search of Squalus. Unfortunately, Squalus’s last transmitted coordinates were several miles from its true location. Thus, the USS Sculpin was headed in the wrong direction and might not have found Squalus at all but for the sharp eyes of Lt. Ned Denby. He thought he saw red smoke on the horizon.

He’d seen Naquin’s emergency signal!

Sculpin found the buoyed phone line that Naquin had sent to the surface and made contact with the trapped men. At this point, Squalus had already been underwater for hours. Unfortunately, the cable between the phone and Squalus snapped, so communication was cut off. Sculpin waited for help to come. Unfortunately, help was miles away at the Washington Navy Yard, then the location of Lt. Commander Charles “Swede” Momsen.

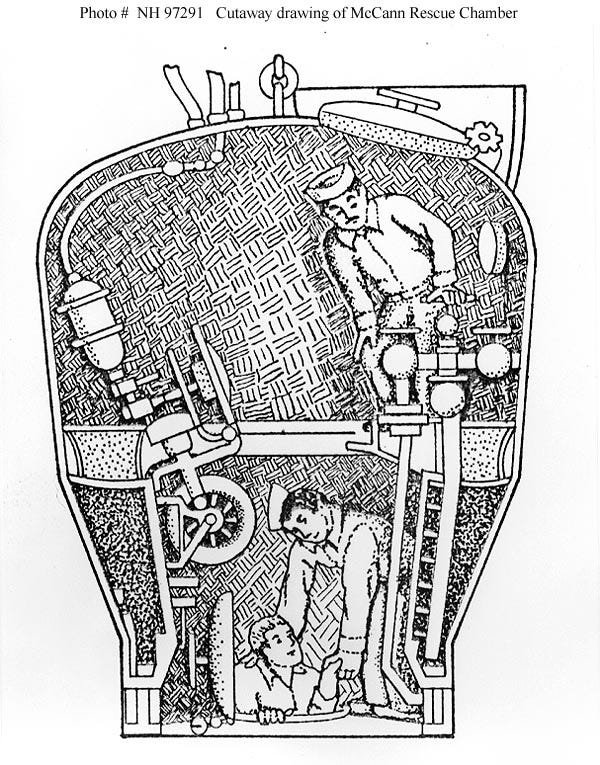

Momsen had been working on a few experimental devices to aid submarine rescues. One of these was the Momsen Lung, a device that could aid breathing. He had also worked on the McCann Rescue Chamber, a so-called “diving bell” that could attach to the hatch of a submarine. Survivors climbed into the bell then rode to the surface, using a cable to guide the bell between surface and submarine.

The bell would now get its chance for use in a real-life situation.

Of course, none of this was as easy as it sounds. Momsen was at the Navy Yard. The experimental diving bell would need to be carried by a minesweeper then in Connecticut. Divers had to be brought in, too. All of this took time. Meanwhile, the country waited with bated breath as the news was transmitted via telegraph. Family members wondered if their husbands, fathers, and sons were alive or dead.

On the morning of May 24, the bell finally arrived and was connected to Squalus’s hatch. Can you imagine how those men felt when the hatch opened and they saw their rescuers? The bell operators brought coffee, soup and blankets. Joking around in relief, the crew’s first response was “Where in the hell are the napkins?” and “Why the delay?”

The first trip was made back to the surface with 7 survivors in the bell. On the second trip, the bell operator made a decision that may have saved lives. He had been instructed to bring back 8 survivors on the second trip. He decided to take more. He took 9 men, ultimately making the last load to the surface lighter than it otherwise would have been.

How fortuitous! The fourth and final trip ended up running into problems. As the last group of sailors was being pulled to the surface, the bell got tripped up on its cable. The cable began to fray. The bell had to be lowered and the cable cut. The last group of survivors was still inside! In the end, the bell was pulled to safety, but it took more than four hours for this last effort.

The Navy salvaged Squalus later that year. It was repaired and returned to service as the USS Sailfish, where it performed admirably during World War II. Believe it or not, some Squalus survivors also returned to service during World War II.

Such a classic American story of perseverance, ingenuity, service—and, of course, success arising from the ruins of defeat!

Sources can always be found on my website, here.

How amazing that the rescue of the Squalus was successful, given the hodgepodge equipment located in various places. The men and women who are submariners are a different breed and I salute each and every one of them.

Submarine duty is a duty filled with risks and unknowns. A dangerous occupation to be sure. I for one would never conquer my clostrophobia in order to dive or even to be locked inside.

Thank you Tara for remembering the sinking and rescue of the Squalus some 85 years ago.

I preferred to sail on top of the ocean or to scuba below the surface but free of the confines of a submarine. I have only encountered a few submariners in my life and came to the conclusion that they are definitely ‘unique’ people.

❤️🇺🇸🇺🇸🇺🇸