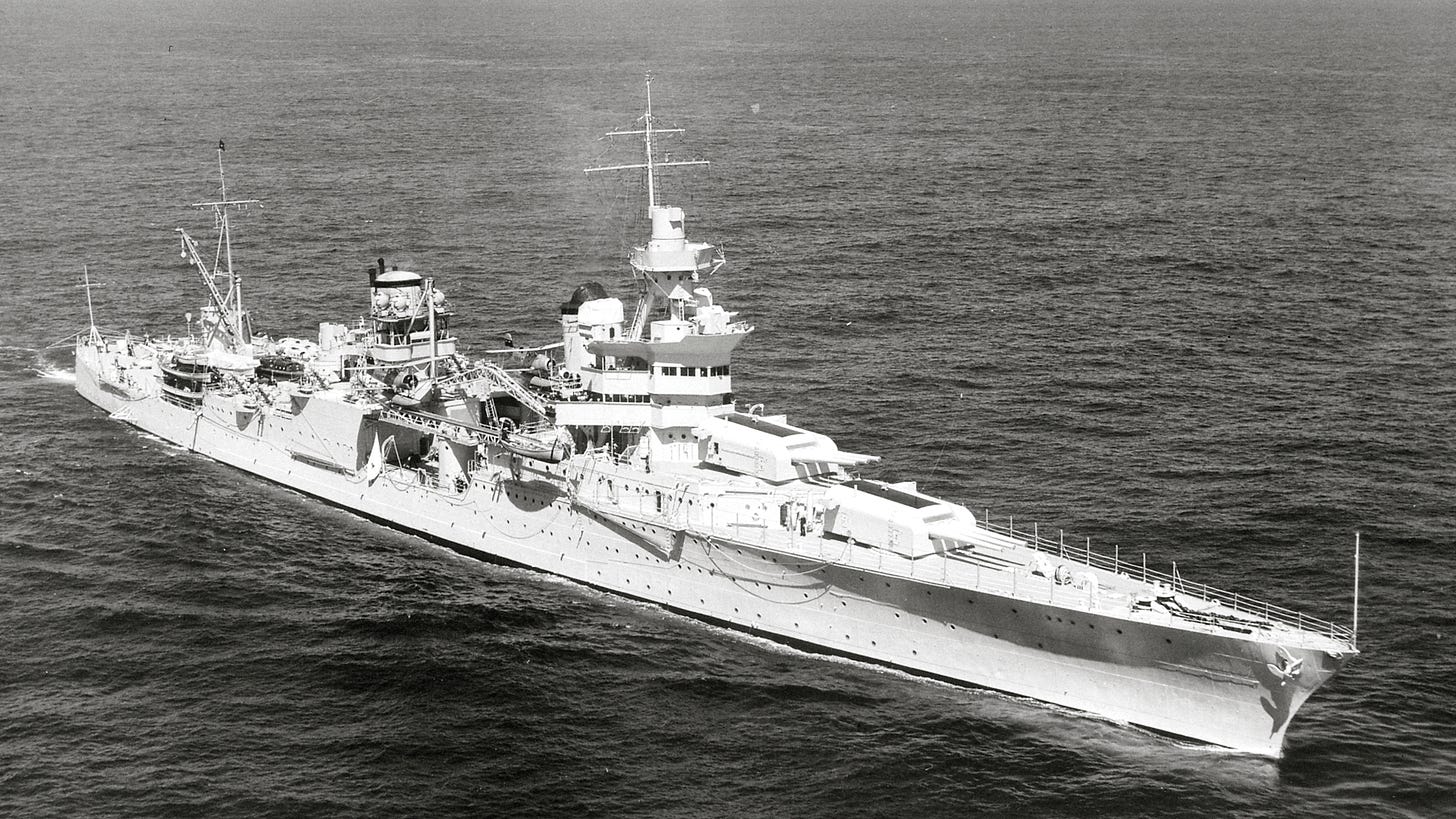

TDIH: USS Indianapolis torpedoed

Indianapolis had already performed the most important part of its mission: It had successfully carried parts for the Little Boy atomic bomb across the Pacific.

On this day in 1945, the USS Indianapolis travels from Guam toward the Leyte Gulf in the Philippines. Unfortunately, Indianapolis would never arrive at its destination. Instead, it was sunk by Japanese torpedoes.

There was just one silver lining to the tragedy. Indianapolis had already performed the most important part of its mission: It had successfully carried parts for the Little Boy atomic bomb across the Pacific. American bombers would soon carry Little Boy toward Hiroshima. In combination with the bomb dropped on Nagasaki, Little Boy would ultimately force an end to World War II.

If only crew members had known what they were carrying! But they didn’t. Instead, Indianapolis completed its delivery of the bomb components on July 26. The ship’s captain, Captain Charles McVay, then continued on to Guam. He was ordered to continue on to the Leyte Gulf.

Unfortunately, the seeds for tragedy were already being sown.

A transmission containing Indianapolis’s expected route was sent ahead to the Leyte Gulf. Unfortunately, a radio staff member there decoded part of the message incorrectly. As a result, the senior officer to whom McVay was to report had no idea that Indianapolis was coming.

Thus, he would not miss her when she failed to arrive on time a few days later.

But that wasn’t the only problem. McVay had requested an escort to the Philippines, but he would not get one. Indianapolis had no sonar capabilities, limiting McVay’s ability to detect Japanese submarines on its own. When McVay heard that he wouldn’t have an escort, he took the news calmly. He’d traveled alone before, and the intelligence report for his voyage indicated that the trip should be routine.

It turns out that two critical pieces of information were missing from that intelligence report. Japanese submarines were known to be operating along his planned path.

Thus, no one was really worried—even if they should have been. It was assumed that Indianapolis could travel safely through these backwaters from Guam to the Leyte Gulf. The ship and its crew left Guam, alone, on July 28.

The voyage was uneventful at first, but the evening of July 29 brought difficulties. Visibility became limited. Indianapolis had been zigzagging through the water, theoretically making it more difficult for a submarine to attack her. But as visibility worsened, Captain McVay ordered a stop to the zigzagging. He had been given discretion to make such a decision, although he was later criticized for making that call.

A little before midnight, a Japanese submarine spotted Indianapolis. Six torpedoes were fired at her just after midnight. Two of these torpedoes found their mark and tore their way through the American ship.

One sailor later described the impact: “Whoom. Up in the air I went. There was water, debris, fire, everything just coming up and we were 81ft (25m) from the water line. It was a tremendous explosion. Then, about the time I got to my knees, another one hit. Whoom.”

One torpedo blew away the bow of the ship. A second torpedo hit near the fuel compartment. The ship exploded—it sank in only 12 minutes! At least one distress signal was sent as the ship went down, but the signal was ignored. Possibly Americans thought that the distress signal was a Japanese ruse to lure rescue ships out to sea.

Of the nearly 1,200 men on board, about 900 men survived the initial explosion and went overboard into the water. They would not be rescued for days.

The story continues early next week.

Sources can always be found on my website, here.

This story is sad for many reasons but especially for the loss of lives and for the mistakes made as you have described Tara. However, I feel compassion for Captain McVay who most likely was not at fault for the sinking of the Indianapolis.

God bless the Indianapolis and its crew. It is a blessing that the ship's main mission had been completed and the war was only days from ending, thanks in great part to the Indianapolis and its crew.

Thank you Tara for a repeat of this very important event during WW2.

It seems odd to me that Captain McVay would not be granted an escort in these hostile waters. Captain McVay can be forgiven his decision to discontinue zig zagging but I would be interested in his superior's decision to refuse an escort and what the status of readiness was in the areas where communications were sent and intelligence was provided. Especially when they knew Japanese submarines operated in those waters. Look forward to the remainder of this piece of history.