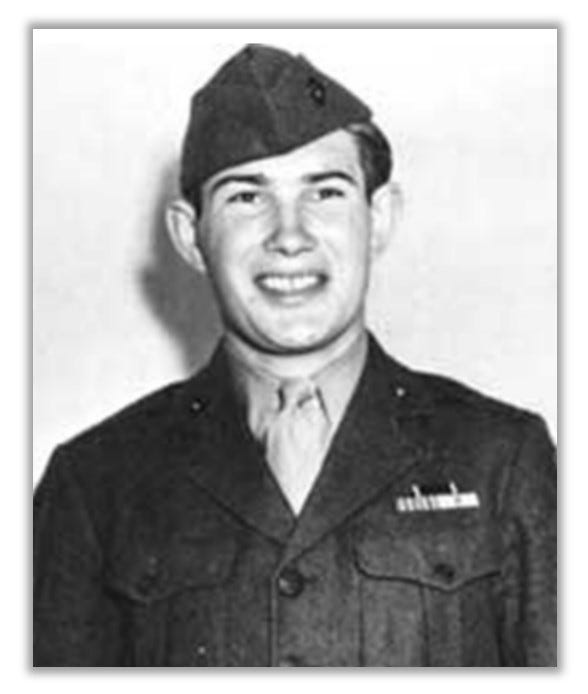

TDIH: Richard Sorenson's Medal

“So I fell on it,” he shrugged, “I could have avoided it. But I thought if it goes off and ruins the five guys that are with me, we could be overrun."

On this day in 1944, a hero receives the Medal of Honor. Richard Sorenson had tried to enlist in the Navy immediately after the December 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor.

“On December 8,” Sorenson later described, “I skipped school and ran down to the recruiting office. . . . I got the papers and everything, but when I came home with them, my parents wouldn’t sign them because I was only 17.”

He turned 18 later that year and enlisted in the United States Marine Corps, but it was early 1944 by the time he’d finished training and been dispatched to the Pacific.

His Medal of Honor action would be his first time in combat.

Then-Private Sorenson was serving in a machine-gun squad with the Fourth Marine Division when it landed on the island of Namur, in the Marshall Islands, on February 1.

About 4,000 Japanese soldiers were defending the island.

“We hit the beach at 12 noon, exactly,” Sorenson described, “under quite heavy fire. The Japanese were great at hiding, and they would crawl under debris and so forth, and then, when we passed through, they’d come up behind us and start shooting . . . .”

Our men were fighting their way across the island, when one battalion spotted a large block house. “And so they set satchel charges against it to blow a hole in it,” Sorenson said, “and then they threw another satchel charge inside. A lot of Japanese ran out the other end.”

There was just one problem. The block house was full of torpedo warheads and aerial bombs. Needless to say, the explosion that followed was enormous. A Marine artillery spotter in a plane overhead at first thought the whole island had blown up. Meanwhile, an officer on the beach remembered “trunks of palm trees and chunks of concrete as large as packing crates . . . flying through the air like match sticks.”

“The battalion commander passed the word to pull back,” Sorenson remembered, “so that they could straighten up the line so that no flanks were exposed. But I was with a group of about 30, and we didn’t get the word.”

Instead, Sorenson’s group settled in for the night, watching as Navy flares flashed around the island. The Japanese attacked again at daybreak. It was a “full-fledged banzai charge,” Sorenson said. But his squad was taking it from both sides. “We fought for about an hour and our troops did not know we were up there, so they were throwing in mortar shells and grenades and a lot of fire,” Sorenson explained. And that’s when he heard someone shout, “grenade!” The young private acted immediately.

“So I fell on it,” he shrugged, “I could have avoided it. But I thought if it goes off and ruins the five guys that are with me, we could be overrun. And the Japanese weren’t taking any prisoners. They were slitting their throats. So that was the end of the battle for me. I laid there about an hour. And a Corpsman named Kirby crawled over and tied off an artery, or I’d have bled to death.”

Sorenson remembers being hauled off on a litter when the other Marines made it to him. But even that wasn’t safe. His litter was soon hit by a Japanese sniper, and he fell off. He was put on a new litter and carried to relative safety aboard a nearby boat, although he doesn’t remember too much about that.

Sorenson spent five months in a Hawaii hospital, then more time in a Seattle hospital. He underwent six surgeries, but he was standing on his own two feet when he was awarded the Medal of Honor. The whole hospital had turned out for the event.

Like so many Medal recipients, he was humble and didn’t seem to think that he’d done anything special.

“Well, somebody had to do it,” he shrugged. “And it just happened to be me.”

Sources can always be found on my website, here.

Another humble Medal of Honor recipient. So many of them and many more brave men and women who haven’t received a medal, but certainly deserve it. Honor to all our brave military heroes. They all should be remembered and recognized.

Greater love has no man...

We can all learn from the self sacrificing attitude in this story of greatness. Many thanks, Richard Sorenson!