TWIH: Operation Vengeance

“In all of American history,” historian Don Hollway concludes, “the only equivalent is the operation that killed al Qaeda mastermind Osama bin Laden.”

During this week in 2001, a World War II pilot passes away. Colonel Rex Barber is best known for his participation in Operation Vengeance, a secret mission undertaken in the Pacific Theater during World War II.

The object of that mission was Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the mastermind behind the attack at Pearl Harbor and commander-in-chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s Combined Fleet.

“In all of American history,” historian Don Hollway concludes, “the only equivalent is the operation that killed al Qaeda mastermind Osama bin Laden.”

It all began with a message intercepted by United States codebreakers on April 14, 1943: Yamamoto was planning an inspection tour of Japanese assets in the Solomon Islands. He would fly from Rabaul, New Britain, to an island near Bougainville early on April 18.

Naturally, Americans responded to this intelligence by planning a mission to intercept him.

Not an easy task! Our men would take a 600-mile roundabout path to avoid detection, and they would have to fly very low over the water to avoid enemy radar. The great distance and low altitudes meant that the task was best suited to the US Army’s 339th Fighter Squadron and its Lockheed P-38G Lightning fighters.

There would be no room for error. The Lightnings could carry just enough fuel to get to and from their destination; they’d have enough fuel for maybe 7 minutes of combat. But what if Yamamoto was late? Or the weather was bad? The margin was so narrow that virtually any unanticipated difficulty could defeat the whole effort.

“At that time, I figured the odds at about a thousand to one that we could make a successful intercept at that distance,” commanding officer Major John W. Mitchell remembered many decades later.

He planned to send 18 planes on the mission: Fourteen would provide cover against the Japanese Zeros accompanying Yamamoto. The other four were the “k iller” group, intended to take out the G4M “Betty” bomber in which Yamamoto was traveling.

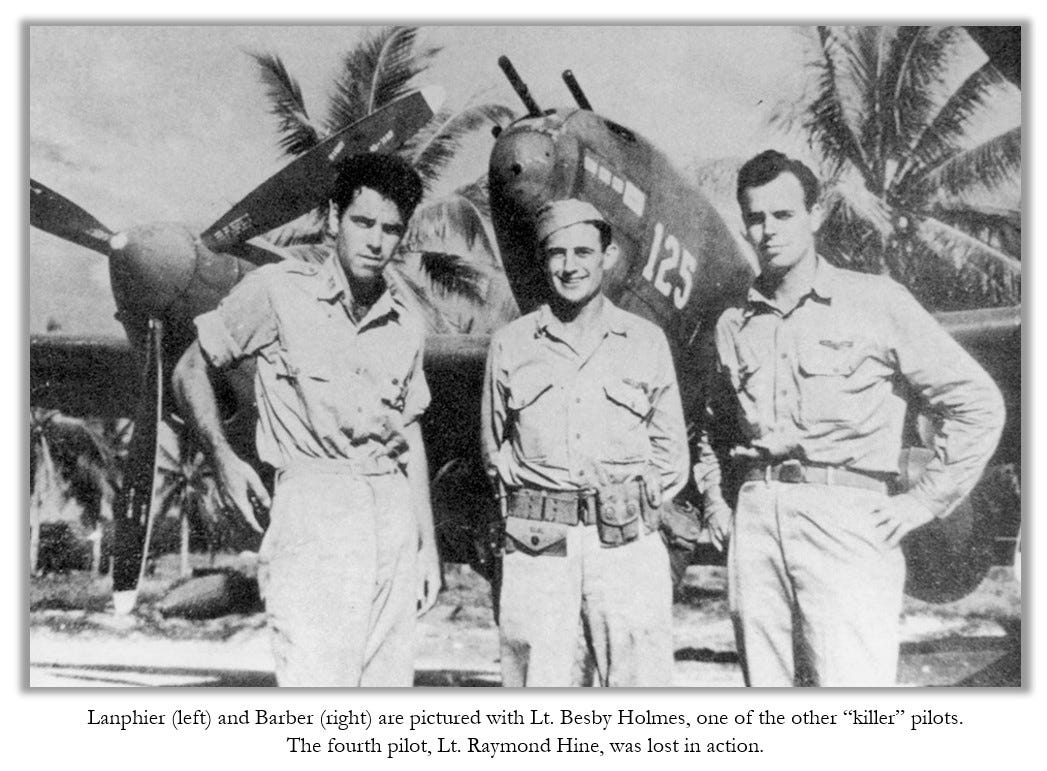

Then-Lt. Barber was among these four pilots, along with Captain Thomas Lanphier, Jr. The mission was top secret, and Barber went to bed on April 17, knowing only that his mission would be revealed in the morning. Nevertheless, he and the other pilots were eager to go when they were briefed early on the 18th.

“They were an eager bunch,” Mitchell recalled. “Everyone wanted to go.”

Mitchell and his men departed at 7:10 a.m., traveling for more than two hours in radio silence. As they approached the planned intercept point, the pilots kept to a low altitude. The dark green planes flying low over the jungle below would be hard to see.

Amazingly, our boys got within a few miles of Yamamoto before they were discovered.

The combat that followed was over in less than 10 minutes. Two Japanese bombers went down in flames, with Yamamoto aboard one of them. Lanphier would take credit for the victory, but Barber also thought he’d been the one to hit Yamamoto.

Would you believe that a dispute over the matter continue for decades?

As things stand today, the pilots officially share credit for downing the plane; however, physical evidence at the crash site, along with testimony from a surviving Japanese pilot, support Barber’s version of events.

Perhaps Secretary of the Air Force Donald Rice said it best in 1993:

“Historians, fighter pilots and all of us who have studied the record of this extraordinary mission will forever speculate as to the exact events of that day in 1943. There is glory for the whole team.”

Sources can always be found on my website, here.

This was an outstanding accomplishment and act of bravery by the men who participated in this mission. Regardless of the pilot who sent Yamamoto to his just reward they were all Hero's.

Brave men risking it all for their nation, their families and their freedom!

Thank you Tara!!