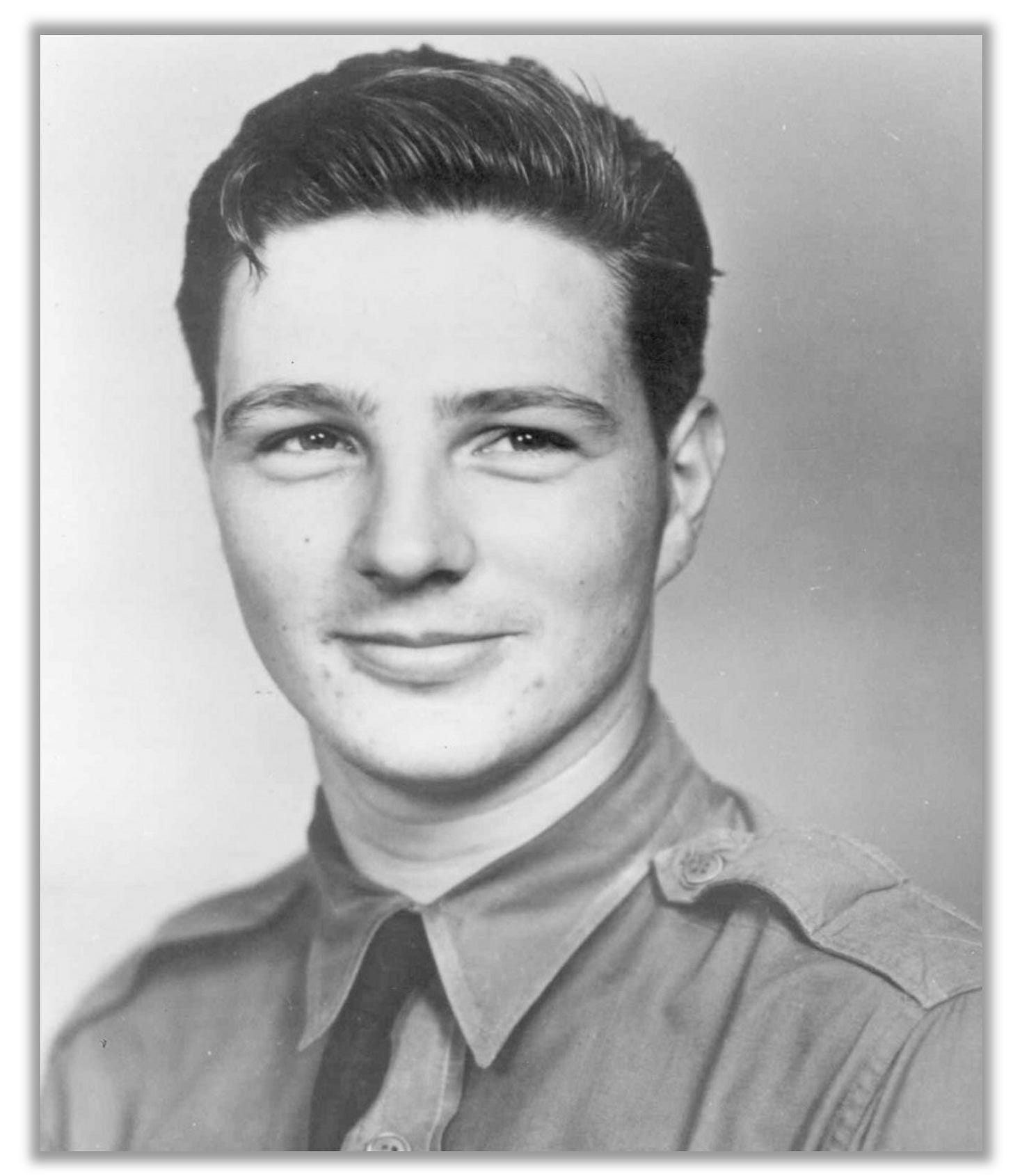

Medal of Honor Monday: Ralph Cheli

Cheli didn’t have to go, but he didn’t want his men in harm’s way unless he was there, too. “[W]hen the mission was going to be tough,” a pilot later said, “we could be sure Cheli would be out there."

At about this time in 1944, a hero dies under unknown circumstances. Major Ralph Cheli earned a Medal of Honor over the skies of the Pacific, but he’d also been captured by the Japanese afterwards.

He’d saved others but had been unable to save himself.

Cheli joined the U.S. Army Air Corps soon after World War II began, dropping out of college and leaving behind his wife and young son. The United States hadn’t yet declared war on Germany or Japan, but perhaps he thought such a moment was inevitable?

The young man was soon an up-and-coming officer with a bright future in front of him. By the summer of 1942, he’d been trusted to lead a flight of B-25s from California to Brisbane, Australia. The flight, an Air Force website notes, was the “first such group to reach combat in an overwater flight.”

Cheli’s heroism came later, as he led two squadrons of the 38th bomb group in an attack on Dagua Airfield in August 1943. As deputy group commander, Cheli didn’t have to go on the mission, but Cheli didn’t want his men in harm’s way unless he was there, too. “[W]hen the mission was going to be tough,” one pilot later told Time magazine, “we could be sure Cheli would be out there with us.”

It was a life-altering decision.

The bombers were attacked almost as soon as they arrived at Dagua, and Cheli’s plane took a hard hit. “The entire right wing and right engine of Major Cheli’s ship were on fire,” Second Lt. Edward Maurer later described. Nevertheless, Cheli remained calm and steady, focused on his targets. He bypassed the opportunity to bail out.

“We were flying so tightly, however,” one pilot observed, “that if he had done so he would have broken up the formation and ruined the attack, besides exposing others to isolated interception. Cheli undoubtedly realized that and pressed his attack ferociously.”

He stayed until the attack was over, then radioed his wingman: “Take the formation home, Pittman.” Cheli turned toward the ocean and brought his burning bomber down. Pittman thought he saw it explode. For a time, Cheli and his crew were believed dead.

At least some of them survived, though. Cheli was found by a fishing boat and taken prisoner. One of his co-prisoners would later remember Cheli’s description of the bomber’s crash landing: “He did not know how he got out of the cockpit, but remembered having to swim to the surface as the airplane was sinking to the bottom. He tried to help his copilot but could not.”

Cheli spent just over six months as a POW. Other prisoners remember that the Japanese guards “really made life hell” for Cheli because of his rank. He was beaten “when he stubbornly refused to answer anything beyond his name, rank and serial number.”

Word got out that Cheli was a prisoner in Rabaul, but then a new story emerged, alleging that Cheli was killed when Americans bombed a ship transporting him to Japan. It wasn’t true, though.

In reality, the Japanese had been prompted to move POWs away from Cheli’s prison when American bombing runs got too close. During this time, Cheli was taken away with about a dozen other prisoners and never seen again. After the war, his remains were found in a mass grave with other soldiers. It’s believed that he was executed in an event known as the Tunnel Hill Massacre.

Cheli received a Medal of Honor, among other honors.

“The real significance of service such as Major Cheli’s,” Lt. Gen. Clarence Irvine said as Cheli Air Force Station was dedicated many years later, “cannot be measured only in terms of gains against an enemy in war. Such a life becomes a lasting symbol of the courage and self-sacrifice to which a man can rise for an ideal, for the love of country, comrades, and duty.”

RIP, Sir.

Sources can always be found on my website, here.

It’s heartbreaking to think that the sacrifices of men like Major Chili are often unknown or forgotten over time. Your contribution in telling the stories of our brave and selfless heroes is deeply appreciated.

It's said that the military grows leaders. I believe that it provides tools to assist, but leadership is something that is inherent in the greatest of our leaders and cannot be taught.