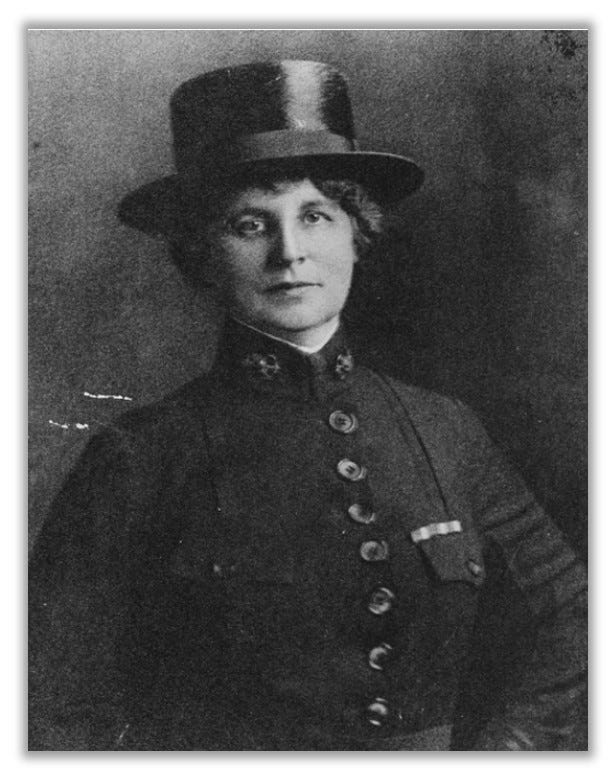

On this day in 1941, a heroine passes away. Lenah Higbee is best known as the first woman to receive the Navy Cross; it was awarded for her service in World War I.

Higbee was a nurse and the widow of retired Marine Corps Lt. Col. John H. Higbee when the Navy Nurse Corps was first authorized in 1908. She was only recently widowed, but that meant she was unmarried—and eligible to serve. Higbee passed the Navy’s written and oral exams and was a member of the “Sacred Twenty” by October 1908.

They were the first 20 nurses in the newly formed Corps.

One of the Sacred Twenty felt as if she were “invading what a man calls his domain.” Nevertheless, the women would prove themselves, as did Higbee when she was dispatched to Norfolk, Virginia, early in 1909.

The commanding officer of Norfolk’s naval hospital had demanded more staff but was unpleasantly surprised when the Navy sent a woman. Nevertheless, the resolute nurse buckled down, working 7 days a week until she’d proven herself.

Higbee spent less than two years as Chief Nurse of that hospital before she received another promotion: She would serve as superintendent of the Navy Nurse Corps, beginning in January 1911.

Let’s just say that the Nurse Corps was never the same again.

When Higbee took over, the Corps was composed of 86 nurses, serving in the United States, the Philippines, and Guam. These nurses were not allowed aboard ships. They didn’t hold a military rank, and they were paid less than men.

Higbee’s persistence helped bring about change—and she did it even as she led her nurses into World War I and through the Spanish Flu that followed.

The first year of war was especially tough. “The cold was awful!” one nurse wrote. “I slept under the weight of six blankets, with four hot water bottles, and shivered. . . . [Nurses] would cough apparently all night; would work all day, and would fall on their cots for another night of coughing.”

But there was still more.

“The wounds which you will be called upon to handle and dress,” another nurse wrote, “are such that you have never imagined it possible for a human being to be so fearfully hurt and yet to be alive.” She noted that “the mental strain . . . is always with you.”

But Higbee was there, supporting her nurses. She developed better training for these women, suddenly expected to witness and treat horrific war injuries. She worked to improve camp conditions. She’d already gotten her women assigned to serve aboard ships, and the ranks of hospital corpsmen grew as her nurses trained them.

The size of the Corps grew exponentially, too. By the end of World War I, a stunning 1,386 nurses were serving.

“No words of mine can adequately describe the valiant way the nurses met the conditions described,” Higbee concluded. Yet her country thought her invaluable, too. She was awarded a Navy Cross.

“Though their contributions to the Navy cannot be measured in ships sunk or enemies engaged,” Naval History Magazine concluded, “Higbee and her nurses were as essential to victory in war as any military element.”

Higbee left an indelible mark on the Corps—and the Navy. During World War II, Navy nurses finally began receiving military ranks. A WWII combat warship was named for Higbee, but a destroyer has been named for her more recently as well. At its 2021 dedication, Rear Admiral Cynthia Kuehner, Director of the Nurse Corps, spoke.

“I am here in no small part because of the vision, initiative and conspicuous achievements of this great warship’s namesake. As the second Superintendent, she led the Navy Nurse Corps with awe inspiring distinction. . . . [W]e celebrate her legacy. We honor her service.”

Sources can always be found on my website, here.

As a retired nurse, I am pleased and proud to read of these achievements. The advances made then shine forward to today's healthcare industry. Nurses play a critical role as always and are called on daily to push the envelope farther. Praise to this great woman.

That was a terrific post Tara. My father was in combat during WWI and fought in the Meuse-Argonne Campaign. On October 4, 1918 he was critically injured with mustard gas which gave him breathing problems for the rest of his life (died in 1976). If one of the nurses hadn’t spotted him moaning he would have been left for dead. I’m not sure if it was one of Lenah’s nurses or a Red Cross nurse but one of them saved my father’s life. A couple of years back my dad, Everett Carney, was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart and other metals to include the Meuse-Argonne Campaign metal. Thank you very much for posting this article and all the others you post. I believe to this day the Meuse-Argonne Campaign is the bloodiest battle in American history.