TDIH: Little-known Revolutionary War Spy

“I shall leave no stone unturned to gain information,” Clark wrote Washington, “tho’ they Inhabitants watch me as a Hawke wou’d a Chicken.”

On or around this day in 1777, George Washington’s spy ring in Pennsylvania gets to work. Maybe you’ve heard of Revolutionary-era spies such as Nathan Hale in New York, but do you know about the Clark Spy Ring in Philadelphia?

“There’s a reason you’ve heard of Nathan Hale but not John Clark,” the Historic Valley Forge website concludes. “Clark was a much better spy.”

Clark worked in both Trenton and New York, operating in the latter city before the renowned Culper Spy Ring was established. Nevertheless, Clark was in Pennsylvania by the time the British seized Philadelphia on September 26, 1777.

Little did the British know it, but George Washington had already foreseen the need for a spy network in the city. Months earlier, he’d ordered Major General Thomas Mifflin to work on exactly that, noting the need for “proper persons . . . who are to remain among them under the mask of friendship.”

Mifflin tapped Clark to take the lead. Clark had grown up in the area and was a natural choice.

“Clark built a large network,” the U.S. Army Intelligence Center of Excellence describes, “of loyal, unassuming men and women, including farmers, merchants, and others in high society who regularly mingled with British officers.”

He also sought Quakers who would be willing to help. Perhaps the pacifists would serve as spies, Clark speculated, if it meant “they should be excused from all military service and fines for nonattendance or not providing substitutes.”

An early report submitted by the Clark Spy Ring revealed just how badly the British had been hurt at the Battle of Germantown on October 4. As many as 200 wagonloads of wounded soldiers had returned to Philadelphia after that engagement, Clark’s report detailed, and a few British Generals had been killed.

“[I]t was the current report in the City,” Clark concluded, “that the Rebels had used the British Troops barbarously. . . . The Enemy have suffered much The Spirits of the Citizens are depressed, & the Country elated.”

In the months that followed, Clark would keep Washington informed about British movements, numbers, morale, and provisions. As the British worked to seize Forts Mifflin and Mercer, on the Delaware, their efforts were complicated by Clark’s constant flow of information to Washington.

“I shall leave no stone unturned to gain information,” Clark wrote Washington on October 27, “tho’ they Inhabitants watch me as a Hawke wou’d a Chicken.”

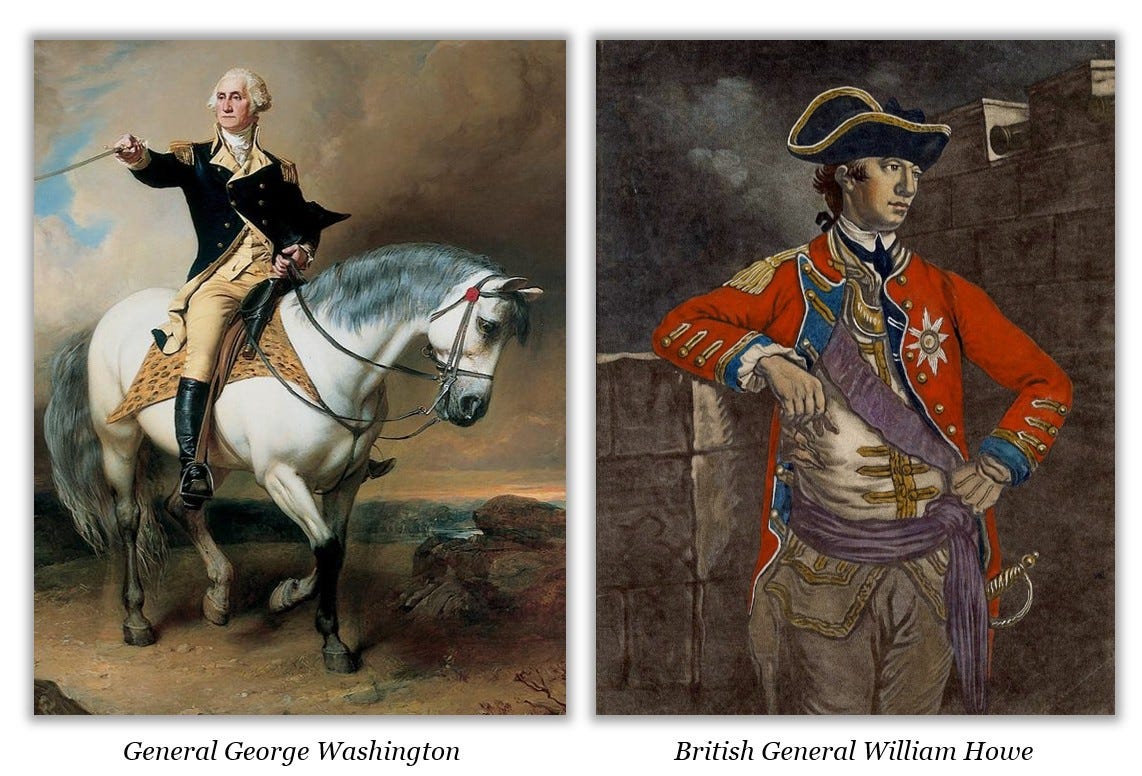

Would you believe that Clark once fooled British General William Howe into giving a spy a pass to travel around freely?

Clark had pretended to be a Quaker who’d been “plundered” by the “Rebels.” He sent a letter via trusted messenger, informing Howe that he “was determined to risque my all in procuring him intelligence” because he was so upset! “[My] Letter was concealed curiously,” Clark later explained to Washington, “& the General [Howe] smiled when he saw the pains taken with it told the bearer if he wou’d return & inform him of your [Washington’s] movements & a state of your Army he [the spy] shou’d be generously rewarded.”

The ruse worked, and Washington ultimately had a connection through which he could feed Howe false information.

Clark worked himself into the ground that fall, and his health suffered. He worried that he might need to retire. Nevertheless, he managed to hold on until December 30.

“[A]s the Armies are both gone into Winter quarters,” he wrote Washington, “I presume nothing further will be wanting in my department—therefore beg your permission to visit Mrs Clark . . . .”

Fortunately, Clark recovered his health. He later obtained a position as auditor of Army accounts with Washington’s help.

Yet another nearly forgotten hero of the Revolution. Where would we be but for patriots such as these?

Sources can always be found on my website, here.

The amazing intricacies of the American Revolution are apparently too many in number to be related in any single volume work. Dare I say that Tara Ross is the one sharing this so aptly and that I for one would love such an extended history of the American Revolution? Clark is one whose story ranks among the best!

“There’s a reason you’ve heard of Nathan Hale but not John Clark,” the Historic Valley Forge website concludes. “Clark was a much better spy.”