TDIH: Amelia Earhart's solo transatlantic flight

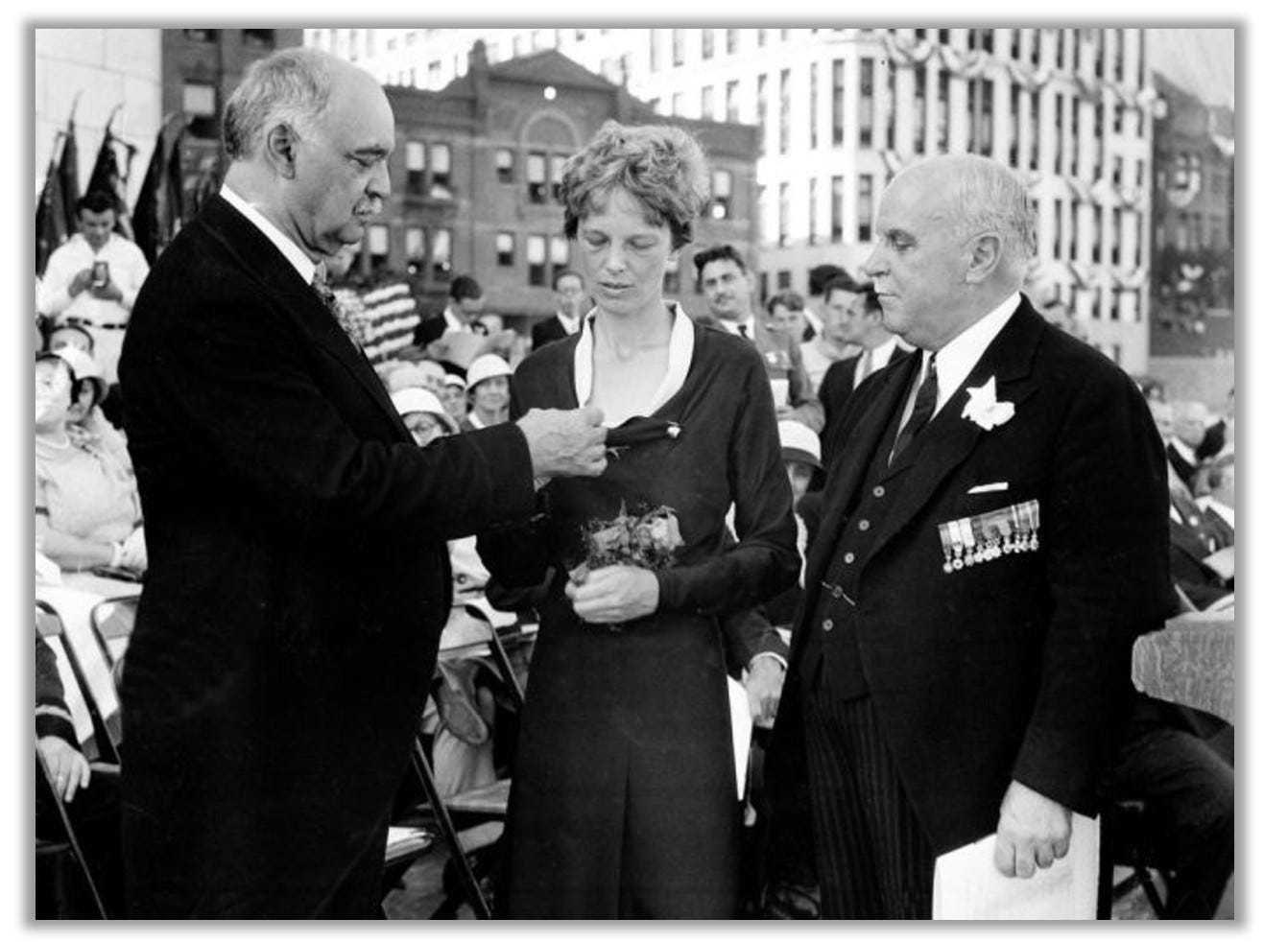

She received a Distinguished Flying Cross for her feat.

On this day in 1932, Amelia Earhart receives a Distinguished Flying Cross. She’d just become the first female—and the second person ever—to make a solo, non-stop transatlantic crossing via airplane.

The talented aviator was already well-known. Four years earlier, she’d earned national attention when she became the first female to fly across the Atlantic. On that occasion, however, she’d been a passenger traveling with two men.

Now she would do it on her own, reportedly declaring that “there’s more to life than being a passenger.”

Amelia prepared for her trip in secret, so that no other female aviator would try to beat her to the punch. She planned to depart on May 20, 1932: Five years, to the day, since Charles Lindbergh’s record-setting flight.

Her plan was simple. She and her mechanic would hop into the back of her Lockheed Vega, out of sight of the media, while her adviser and fellow pilot Bernt Balchen flew it to Newfoundland. Amelia would then begin a trip across the Atlantic, alone.

Balchen described Amelia’s final moments before take-off.

“She looks at me with a small lonely smile,” he wrote in his diary, “and says, ‘Do you think I can make it?’ and I grin back: ‘You bet.’ She crawls calmly into the cockpit of the big empty airplane . . . . We pull the chocks, and she is off . . . . ”

It wasn’t long before Amelia ran into trouble. Just a few hours in, her altimeter quit working. “In all her experience of flying,” Earhart biographer Mary S. Lovell writes, “she had never had this happen before and [her husband] George later wrote that her reaction was one of awe rather than horror.”

An unexpected thunderstorm presented the next challenge, but getting tossed around would not be Amelia’s biggest problem. “The manifold on her engine broke,” Doris Rich, another biographer, explains, “and the flames from the backfire from it were coming out.”

Would more problems arise? Should she turn back? No, she decided.

Later, Amelia was climbing to a higher altitude to get around clouds when her Vega spun out of control due to an accumulation of ice. “How long we spun I do not know,” she later said. “I do know that I did my best to do exactly what one should do with a spinning plane and regained flying control as the warmth of the lower altitude melted the ice.”

The rest of the night proved difficult, and George would later tell reporters that “it was absolutely black, and she flew blind.” At various points “she flew right on top of the water” because “she’d rather drown than burn up.” Yet there was more bad news when dawn broke: She had a gas leak! She’d intended to fly the whole way to France, but now that wouldn’t work.

Instead, Amelia touched down in a pasture near Londonderry, Ireland, as an astonished farm hand watched. “Have you flown far?” he asked. “From America,” she replied.

Amelia found a phone and reported her success to reporters in London. She’d completed the trip in less than 15 hours.

“I’m not a bit hurt and I think the plane is all right,” she said. “I had trouble with my exhaust manifold . . . . for a lot of the way I was flying through storms—mist, rain, and a little fog. . . . I’m a bit deaf after the terrible roar of the engines in my ears all the time, but at any rate I’ve done it.”

Naturally, the daring stunt made Amelia even more beloved than she was before. As a civilian, she wasn’t technically eligible for a Distinguished Flying Cross, but Congress approved the award anyway.

“I did this just for fun,” Amelia concluded. “I have always wanted to do the flight myself and my husband is a good sport. He does not interfere with my flying and I don’t interfere with his affairs.”

Sources can always be found on my website, here.

I have flown across the Atlantic (never solo) hundreds of times in MacDonald Douglas F-4, Airbus 310, and Boeing 767 & 777 aircraft. It amazes me how complex the coordination and planning modern crossings actually are. For early aviators to have done it with little to no support is most impressive and an actual death defying feat!

Such a great story, well retold! Earhart was the first lady to do this, braving the dangers and through it all moving aviation forward. We owe her and the other pioneers a debt of gratitude.