TDIH: Dogs for Defense

“Other countries have used dogs in their Armies for years and ours has not. We’ve got to do it. Just think what dogs can do guarding forts, munition plants, and other such places.”

On this day in 1942, a Georgia newspaper reports on a new military effort: Dogs for Defense. Did you know that some Americans offered their family pets to help during World War II?

“Great progress is being made in preparing a dog corps in America that will be second to none,” an Atlanta Constitution journalist described. “It is estimated that one trained dog can release from three to six men who would otherwise be needed for guard duty.”

Dogs for Defense was founded by poodle breeder Alene Erlanger in January 1942, soon after the attack at Pearl Harbor. “Other countries have used dogs in their Armies for years and ours has not,” she said. “We’ve got to do it. Just think what dogs can do guarding forts, munition plants, and other such places.”

Those who supported Dogs for Defense were dog lovers who knew the strengths of our canine friends: They included “breeders, trainers, professional and amateur; kennel club members, show and field trial judges, handlers, veterinarians, editors, writers; in short, people who have to do with dogs,” historian Fairfax Downey describes.

By March 1942, Dogs for Defense was authorized to deliver 200 trained sentry dogs to the U.S. Army. Ultimately, tens of thousands of dogs would be donated and trained to help our military.

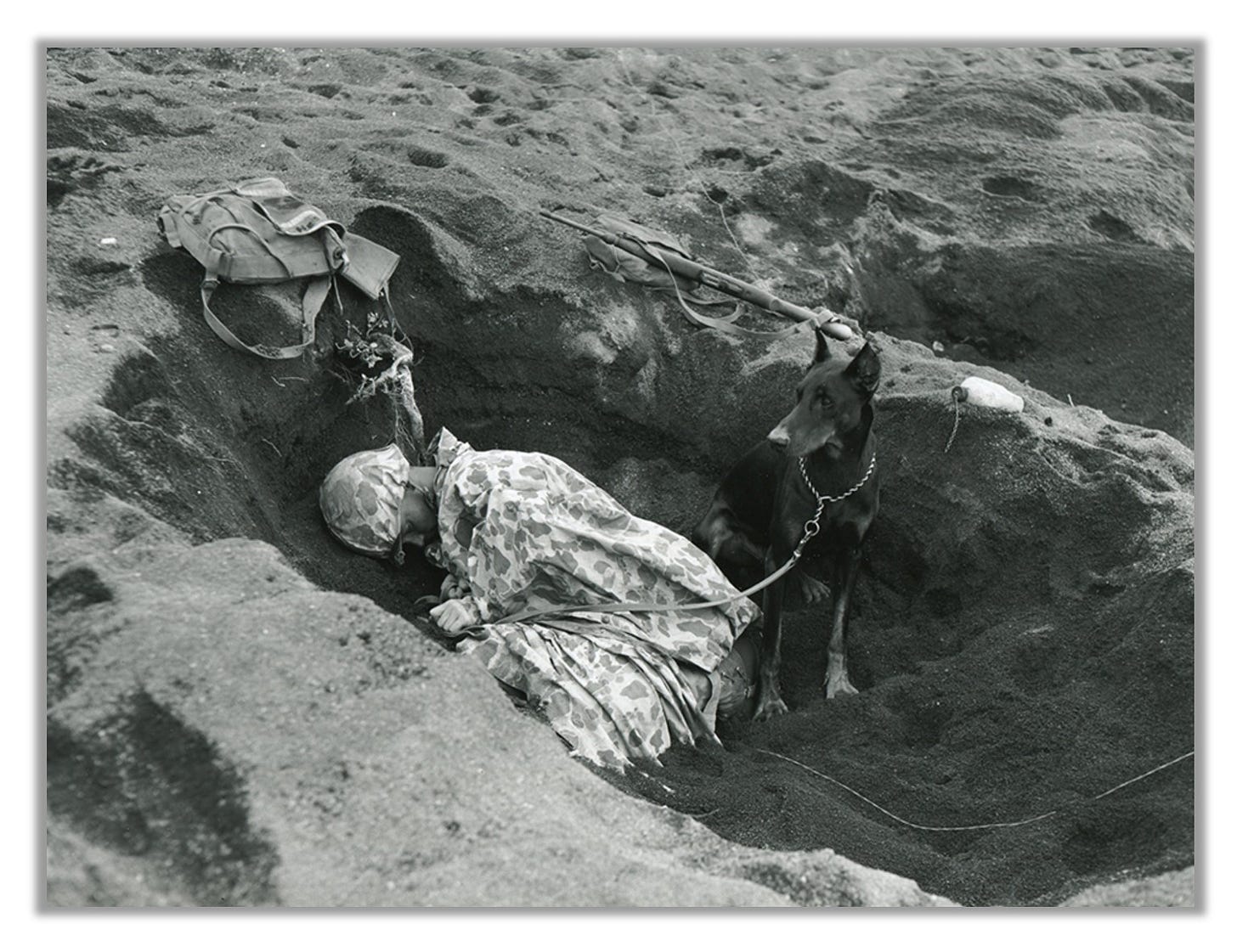

After donation, dogs were evaluated by Dogs for Defense, which had height and weight requirements for the dogs. The Army also preferred breeds with the right skill set. For instance, German Shepherds were considered good for guard duty and Siberian Huskies could help as sled-dogs.

Dogs that didn’t pass physical examinations were returned to their owner. The rest entered specialized training as messenger, sentry, scout, attack, or guard dogs. Dogs were trained to respond to verbal cues, but they were also trained to respond to hand signals. They knew that a work collar required a certain level of diligence, whereas a regular collar meant a dog could rest and relax.

Newspapers, radio programs, songs, and children’s books encouraged Americans to donate their pets. “Pride fighting down sorrow, as you send your ‘soldier’ away to the wars,” one ad noted under the headline “Shep will show ‘em…”

The lyrics for another song mourned that “I'll get along somehow / If my country needs him now / I’d like to give my dog to Uncle Sam.”

Indeed, to the Greatest Generation, donating a dog was nothing if not patriotic.

Dogs were trained for the battlefield, naturally, but you won’t be surprised to hear that there was a softer side, too. In one notable example, Dogs for Defense found a German Shepherd puppy for a hospitalized airman who’d been feeling glum. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the wounded airman began improving much faster once he had a puppy around. He recovered six months faster than his doctors had thought possible.

Other patients in the hospital soon had dogs, too.

After the war, dogs were trained for reentry into civilian life, then they were returned to their owners where possible. Meanwhile, Dogs for Defense ensured that “orphaned” dogs were adopted. Many of those dogs ended up with the handlers that they’d come to know and love while overseas.

Families were happy to have their dogs back, but proud of the service provided, too.

“Thank you for your good care and training of our dog, MIKE,” a Mrs. Edward Connally of Utah wrote the Quartermaster. “He knew all of us and still remembers the tricks he knew before he entered the service. My son, Edward, an Army officer, and all of us are proud of his honorable discharge and his deportment.”

Yet another unique way in which the Greatest Generation loved and served our country.

Sources can always be found on my website, here.

I’ve never heard this story. I loved it!! Thank you to our families “who served” through their furry family members! ❤️

👍👍👍